In volcanoes, or perched on a precipice of a Swiss Alp – that’s where Bond lairs should be located. But if Sam Mendes were looking for a new baddie abode for the next Bond flick, TopGear has found the perfect spot.

It’s not the usual aluminium-furnished glass box, rather a corrugated enormo-shed in rural Japan just a few hours north of Tokyo. But it does have a few surprises.

Ahead of me there are lasers. To the left and right of me, lasers. Behind me – you guessed it – more lasers. All cutting, machining, welding and piercing titanium to millimetric precision.

A smattering of faces hide behind surgical masks. They’re making parts for new technologies that harness energy from temperature changes in the sea. All that’s missing is a man overseeing his empire from a leather-backed swivel chair while stroking a white Persian cat.

Blofeld never turns up. A man arrives and bows while clutching a car registration plate under his armpit. Then bows a bit more, before passing me his business card. “Takeshi Moroi – President,” it reads.

Mr Moroi, 55, is an entrepreneur and owner of M’s Vantec, an industrial sheet metal fabricator. He – alongside his legion of lasers – is responsible for making the tiny holes in flatscreens, from diddy TVs to giant jumbotrons. Turns out to be quite a profitable trade. Something well demonstrated as he leads me to the lair’s second level

“Work downstairs. Play upstairs,” he says as the service elevator’s display dings onto the second floor. A double-height door peels open to reveal a car collection so varied it leaves Beaulieu red-faced.

Mr Moroi’s haul currently hovers around the 40-car mark. Ex-Le Mans Ford GT40s, Ferrari GTOs, a Merc 190E DTM car plus AMG Hammer, limited Lancia Integrales, a pack of Porsches, Corvettes… the list goes on and on and on.

“Since I was a young child, I’ve always had an obsession and passion for cars,” he says. “It started with the Toyota 2000GT, a pure and classic design that sucked me in.”

A design so captivating, he now owns seven. Three of which, plus a host of Ferraris and Porsches, currently sit in a workshop at the far end. As it turns out, all those lasers and that manufacturing hardware downstairs are quite handy for making one-off parts for rare cars.

We then take a tour of a collection on the opposite side of the building. That’s the bit where his friends’ cars are kept.

Peking-to-Paris Bentleys, furiously expensive early Bugattis, a triumvirate of magical Mercedes 190 and 300 SLs – all tease bodywork through their silk negligee dust covers. Then we’re interrupted.

A mechanical minion has been summoned over. A short exchange follows – one punctuated by handing over the numberplate that Mr Moroi has been clutching throughout.

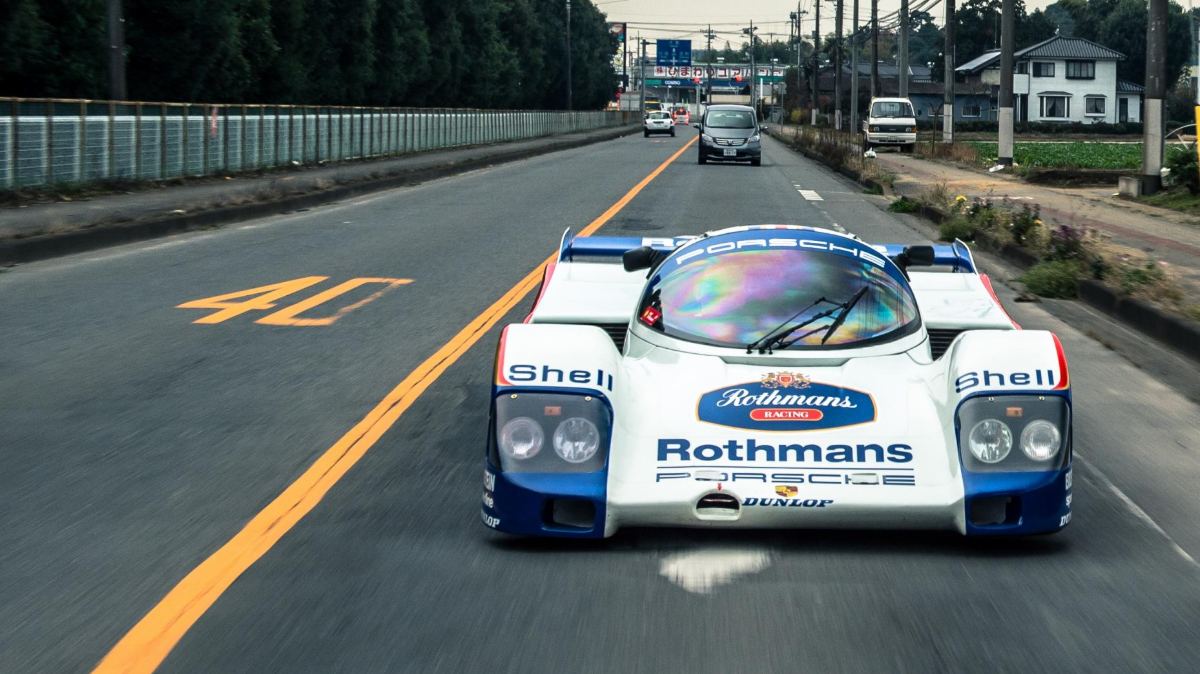

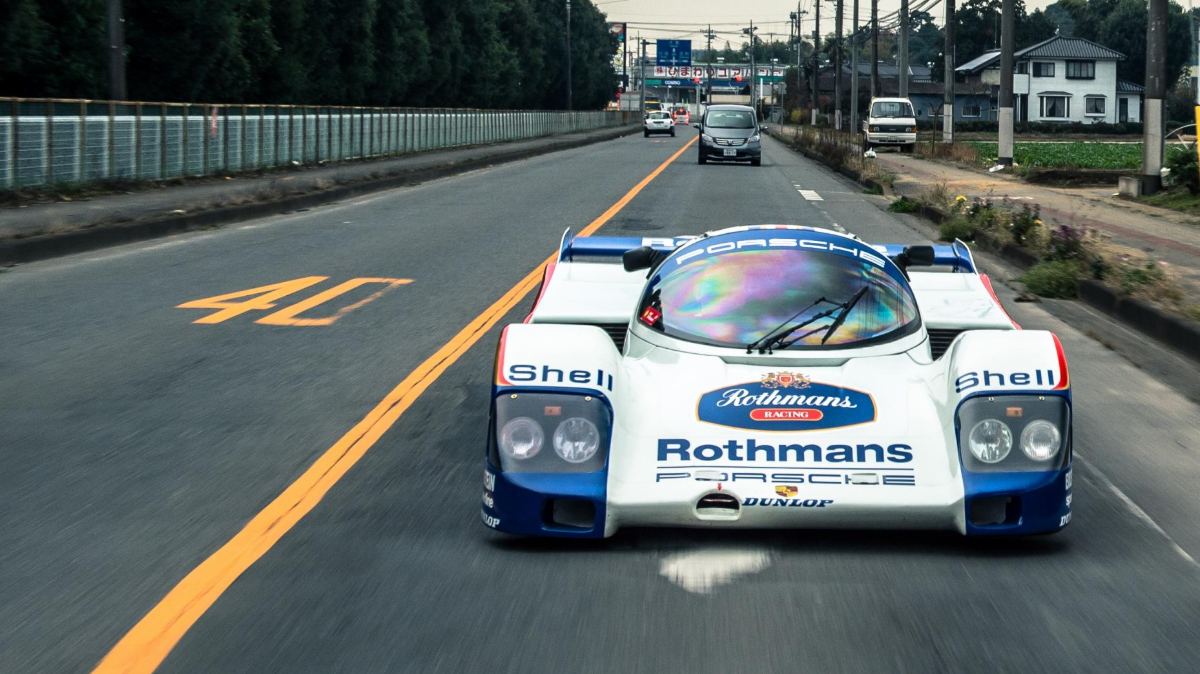

Four mechanics grab a fistful of screwdrivers, walk over to a Rothmans-liveried Porsche 962 race car, remove the rear clamshell and attach said plate to the back of the car. Now, the phrase “racecar with numberplates” gets batted around regularly, but this is something else.

“I love the Group C aesthetic and purity of design,” Mr Moroi says with a race-winning Taisan 962 JGTC car a couple of feet away, as well as a Mazda 787B’s shell somewhere behind that.

He grew up watching the 962 – together with the closely related 956 – dominate motorsport in the Eighties and early Nineties. Both Porsches won 232 races across 12 years, including seven victories at Le Mans – enough to give them legendary status and make him want to own one. And when he could, he did. A pretty rare one too.

See, in the late Eighties, Porsche announced that it would no longer support the 962 as a works team. But that didn’t stop privateers snapping up 962 tubs and having a go themselves. One of them was Porsche’s 1983 Le Mans-winning driver, Vern Schuppan. With Japanese backing, the Australian racing driver produced carbon-fibre – rather than aluminium – 962 moncoques in the UK, with the intent of putting them on the road. A bonkers but utterly brilliant idea.

Moroi’s car is one of two Schuppan prototypes, distinct because it’s clad in the same long-tail carbon-Kevlar body as the racing cars. The later production cars, of which there were only five (some say six) and sold for close to £1m each, had round headlights and bubbly, curvaceous bodywork.

Under the bodywork of the Rothmans car is a complete jumble sale of 962 and 956 mechanicals. The suspension is from a 956, as is the dry-sumped 935/82 2.65-litre flat-six engine. A twin-turbo lump good for 630bhp – enough to send the slippery body shape north of 230mph.

But even though it looks like a racing car, sounds like a racing car, and has the innards of a racing car, under the eyes of the Japanese law it’s a road car. Handy, considering Mr Moroi has run out of milk.

He shouts to one of his mechanics in Japanese. I imagine it’s something along the lines of, “We’re popping to the shops, mate. Do you want anything?”

With this, he hops his left leg over the bank of radiators in the 962’s flank, grabs the sidepod with one hand, then loops the other leg across and over like a ballet dancer and slithers in. It’s a good thing Mr Moroi isn’t the tallest…

A sweat-soaked and shaggy Momo Alcantara steering wheel dominates the bare carbon cockpit. Behind it, the clocks canted to read 300kph at the dead ahead. Down to the right, a manual gearlever; 5spd, dog-leg first with the exposed linkage running down the door sill.

Beside the driver, a skinny passenger seat with onboard entertainment: a tiny but busy boost gauge readout. A fire extinguisher is lashed to the dash (just in case) while a front numberplate fills the footwell. Not exactly comfy, but there is air-conditioning. Bet the racers at Le Mans could’ve done with that.

“It’s quite easy to drive on the street,” Mr Moroi says with a smile. “But scary, and that’s what I love.”

With that, he turns a key and fires it up. A racing car started on a key – that feels alien. But as soon as the car is transported by service elevator back to reality downstairs, things get properly extraterrestrial.

Sat in the semi-agricultural surrounds of the Gunma Prefecture, the 962, despite its numberplates and blinky indicators, doesn’t look any less ridiculous

It’s quite easy to drive on the street,” Mr Moroi says with a smile. “But scary, and that’s what I love.

Watching it pull onto the road gives a sense of scale for the first time. It’s wide enough to fill a whole lane, but so low its flared shoulders barely come up to a truck’s wheelnuts at traffic lights.

More at home kissing kerbs at Fuji Speedway, now negotiating kamikaze kei trucks at four-way intersections, you’d think the 962 would be an utter b*****d to drive on the road. But it’s surprisingly good at soaking up Japan’s corduroy tarmac.

But in stop-start traffic, things get a bit hot and whiffy – rather unsurprising given that it’s air-cooled and happy sitting at over 200mph on the Mulsanne Straight.

Time to raise the pace and get some air into the thing. With a clear road ahead, Mr Moroi floors the throttle. There’s enough time to count multiple Mississippis as the turbos spool up. Then, BAM! The car shoots up the road – largely sideways – in a giant whoomph. But this isn’t Mr Moroi’s first rodeo. Instead of broadsiding a merchant of mouldy oranges, he grabs another gear and charges harder.

Not much can prepare you for seeing a Le Mans lookalike bombing by paddy fields. With the frenetic, frantic engine singing at 8,000rpm, it’s a sight normally only possible once hardcoded into a videogame.

But the locals barely bat an eyelid. They’re either incredibly au fait with unqualified weirdness – something a night in Tokyo’s Akihabara district will quickly confirm – or just immensely polite. Not one cameraphone is brandished from its holster. Even when we roll into our neon-twinkling destination: a konbini, or convenience store.

They’re round-the-clock purveyors of obscure boiled, fried and dried food, somewhere to do your banking, buy a dubious anime book and pretty much everything else you can imagine. Including milk.

Given you need an air traffic control tower and marshals with table tennis bats to reverse-park, Mr Moroi slots the 962 nose-first into a vacant parking spot before slipping out and admiring the streamlined Group C silhouette as it ticks itself cool.

As mad as the situation already is, I want to know if there’s anything else he wants to add to his automotive armoury. “I want an F1 car,” he replies. “One of my greatest experiences behind the wheel is feeling the downforce in my 962s; I want to know what it’s like in an F1 car.”

There’s a Japanese phrase that sums up my mind-frying few hours with Mr Moroi: ‘otaku’. Traditionally used in the surrounds of manga and anime, it describes über-obsessive and ultra-informed subculture fans. Mr Moroi is the embodiment of automotive otaku. He’s got an addiction to cars and wants to exploit them for all they’re worth.

With an unabating craving for cars, and an F1 car on the wish list, there’s only one thing for it: FIRE THE LASERS!