The aim is so drastically out of the ordinary as to be scarcely credible. Adrian Newey, working with Aston Martin, says he will build a road car with performance vastly beyond any hypercar the world has known.

Around a track, the target is a lap time comparable with current top-level race cars – Formula One or Le Mans prototypes. Can this be so? “It is correct.” My eyes widen. Newey qualifies slightly. “Just to be clear, there will be two variants. The road-going variant and the track variant. Although the track variant will be a very close relation. It’ll have, as you might imagine, slightly bigger wheels, bigger wings, to achieve that level of performance. But the road car, I think, is a very different car to anything that’s out there at the moment.”

This is said in the softly spoken, professorial tones used by an engineer whose career has been at the very sharpest end of designing the quickest racers of all. Adrian Newey OBE is responsible for 10 Formula One constructors’ championship-winning cars – for Williams, McLaren and Red Bull. Just the sort of fellow you’d want to be engineering a road car (or a version of a road car) that, in a minute’s lapping, would leave a Porsche 918, McLaren P1 or LaFerrari perhaps 10 long seconds adrift. The biggest beasts of the current megacar kingdom duke it out for the advantage of the odd second or two over a seven-minute ’Ring lap. The performance jump Newey is discussing is all but unimaginable.

And yet is he the man for the job? He says he bought himself a V12 Vantage as a reward for winning the 2010 championship, and tactfully doesn’t mention he also has a McLaren F1 GTR. But does he really know the restraints and restrictions of road-going cars? I meet him alongside Aston Martin’s creative director, Marek Reichman. For a year now, the two have been collaborating on the AM-RB 001. AM is Aston Martin. RB is Red Bull, or, more specifically, Red Bull’s Advanced Technologies division, run by Newey and also consulting to Sir Ben Ainslee’s America’s Cup campaign. It sounds like a helpful combination: one knowing road cars, the other racers, both operating at the very top level.

And yet… this performance leap still sounds ridiculous. Reichman says the car can succeed because it begins from an absolutely blank sheet. Other cars, he points out, “don’t have the purity and light weight and almost one-to-one power-to-weight relationship as their starting point. They are based on something that exists.” Or else the cars concerned are adulterated by other irrelevant strategic aims of their manufacturers.

One bhp to one kg eh? A thousand horsepower per tonne. Even if that’s the track-only version, it’s a seachange from a McLaren P1 GTR’s 687bhp per tonne, the current state of the art. So you’re going to have to make huge power increases or huge weight cuts? Newey acknowledges that much, without saying quite how, but mentioning a rethink of packaging. Is it even a two-seater? “Two seats, yes,” says Newey. Side by side? “Yes.”

At which point the very tall Reichman intercedes. “And I fit.” So has it actually got a roof? “Yes.” The road version also has a stereo and so on, they say.

It won’t be shatteringly uncomfortable. Newey again: “Given my background, and Red Bull’s background, then the easy thing would be to design a road-going LMP1 car. But if it felt like that on the road, I would feel we’d failed. So we tried to create a car of two characters. A car that’s capable of very extreme performance when you want it to be, but equally if you’re stuck in a traffic jam on the King’s Road it’s still a comfortable place to be. Marek and I would like it to be a car that, if you want to commute in it, you can.”

A full-size clay model of the car now exists, and Reichman wants to stress that it doesn’t look like a mad wind-tunnel experiment. “Going back to the analogy of an LMP1, in many ways that has a brutish nature because its form language is following a function. But this car won’t just be comfortable, but beautiful to look at in that traffic jam too. That’s an important side of this. It doesn’t have the constraints of having to follow a formula. We can put together the art and science of aerodynamics and the art of beautiful design.”

Aerodynamics is clearly a vital source of its abilities. Reichman tantalisingly adds, “Half of the car is the underside and you see quite a lot of that – but I’m probably saying too much.”

Freedom from the constraints of race codes is appealing to Newey too. He knows a road car must meet safety, emissions and noise rules. “But you’re allowed far more freedom than the current Formula One regulations, which are much too restrictive on the chassis. If you painted all the cars white, it would take a bit of a Formula One expert to tell which car is which.”

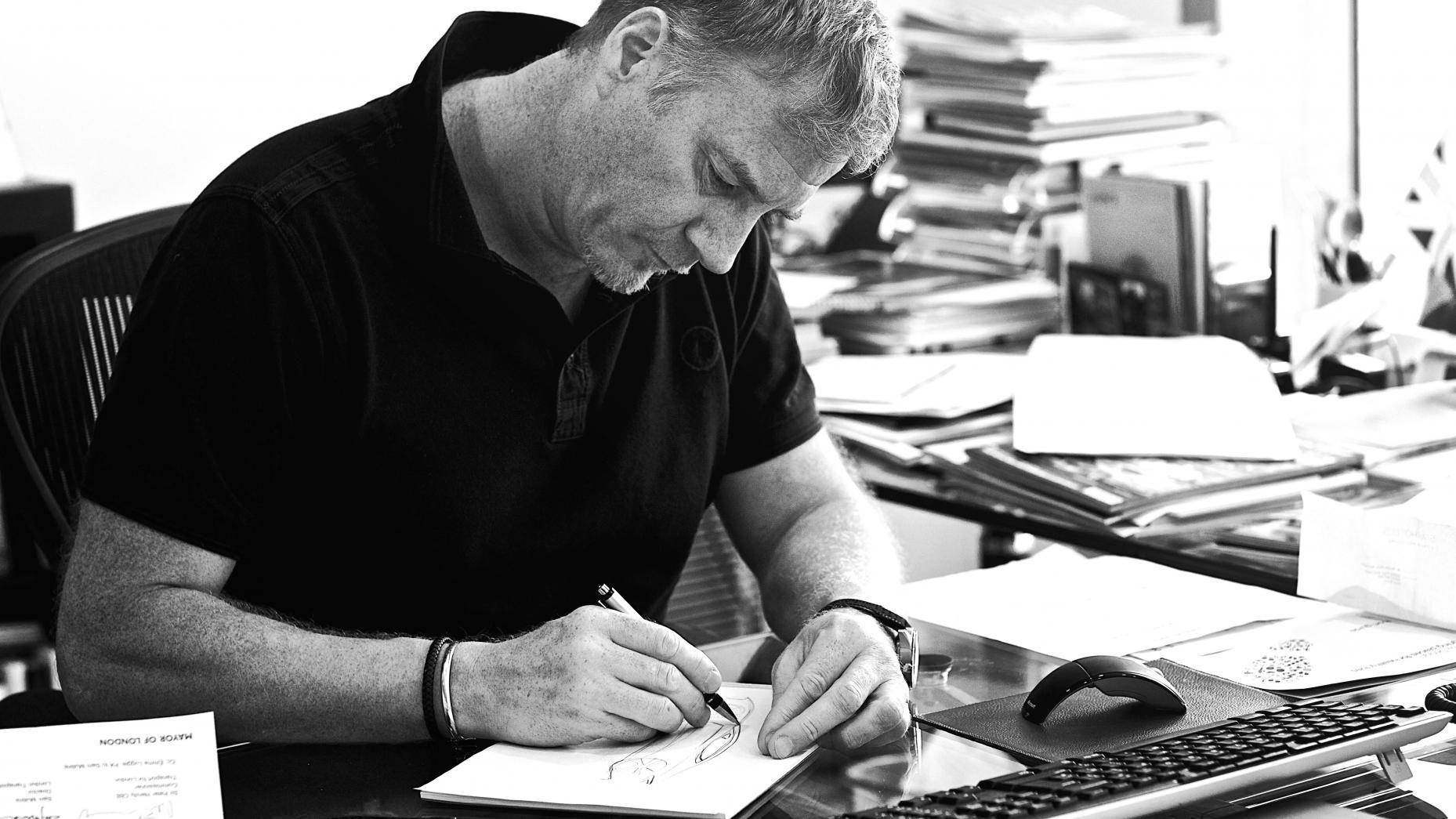

As to the look of the AM-RB 001, so far all we have to go on is an agonising tease of a sketch, a few enigmatic brush strokes. Will it look like an Aston? “Yes,” says Reichman without hesitation. And then, at length, “An Aston Martin is very much about the dynamic language of its surface telling you it’s an Aston. Does it look like an Aston? Yes. Does it look like one you’ve ever seen before? No.”

That’s fair enough because, except for the polyhedral Bulldog one-off, the firm has never done any mid-engined cars. Which this is. And Red Bull hasn’t done a road car. So this truly is clean-sheet. No twin-turbo V12, for instance? No, Reichman insists everything in the car is “completely unique”.

Reichman isn’t just a designer. He’s also raced and knows engineering. Even so, it’s surprising how much the two men seem to have arrived at a convergent view about what this car should look like. “Without BS,” says Reichman, “The first time we met to show and share, it wasn’t a hundred miles apart.”

Newey agrees, in almost touching terms. “As Marek has said, we both had completely separately come up with our ideas for what such a car should look like. As it turned out, the basic proportions were very similar. The one we’d come up with was slightly smaller,” – no surprise there – “But it was very similar. So that marriage actually was very simple. Sometimes when you put two companies together it’s kind of shotgun, and sometimes it works very easily. I think this is the very easy category. We seem to have the same thoughts, the same ideas.” Aaaaaw shucks.

Reichman continues. “My view on aesthetics is that purity, simplicity and proportion are important. If you look at the proportion of 001, it is near to perfect in terms of balance because it’s perfectly balanced from a performance perspective, in chassis balance and occupant versus midships engine package.” I stop him. “Engine”? Not, in racecar parlance, “power unit”? He corrects himself. “A lump.”

Newey elaborates, while remaining as maddeningly non-specific as you would expect given we’re having this conversation at a remarkably early stage of the project’s life. “There are things you can do with hybridisation that offer some very interesting areas to explore. We’re looking at things which haven’t been done using that technology.”

So they’ll spill no specifics on power or weight. It’s going to be made all the more mountainously difficult because they want to meet the boring road-car requirements of robustness. A racer has to be strong for two hours on a Sunday, but in a very tightly controlled set of conditions. Anything can befall a road car out in the wild, and preparing it for those rigours will surely undermine lightness and performance. Also, it can’t demand 15 technicians with laptops just to start the engine. Newey doesn’t shirk. “Exactly. Understanding the duty cycles that a road car would be expected to cope with – cobbles, going up a kerb – it has to do all that. You can’t have the front wheels falling off.”

If the surfaces and use-cases are more variable for a hypercar than an F1 car, the driver is even more so. The driver is qualified not by being championship material, but by wealth. Does that affect the car technically? Newey nods. “We’d be very keen that people who drive this car become familiar with it. With a car of that level of performance, it’s important to build up a databank of experience in how to get the most out of it. To do that, you have to take the car on a track. That’s obvious.” Of course, Aston has been doing just this driver coaching with its Vulcan programme.

Only 99 of the road-going AM-RB 001s are planned, plus an unspecified number of the track cars, so the owners will doubtless get pretty special treatment. The track cars aren’t just a simple kit of parts away from the road cars. Says Newey, “If you kept swapping parts, you could convert one to the other. But to me, to both of us, you’re buying a product, so why would you then want to cut it around and try to make it something different?”

So few cars. Such amazing performance. Where is the price, seen against the realm of hypercars we know today? “Wait and see,” says Newey. Can he choose any material and any construction method to get the performance they want? “Within reason. There’s still a budget to work to, just as a Formula One team ultimately has a budget to work to.”

But so far we don’t know anything specific about those exceedingly precious materials, finely wrought components or intricate systems. There is still so much to learn about the AM-RB 001 that for it to reach its intended performance still sounds, candidly, like some crazed fantasy. Still, at least we know the people behind it are aware of the hurdles that stand in their way. And they’re among the best brains for the job. They have given themselves until 2018. From here on in, it could get wildly exciting.

- Paul Horrell